The purpose of these interviews was to gather data on transit use, frustrations, opinions, and improvement suggestions from a group of vision-impaired subjects (Golledge et al., 1995 ; Golledge, 1996; Golledge et al., 1997 ; Marston et al., 1997) . These data were needed in order to frame more specific future studies. The subjects reported a high degree of frustration when using transit, and the most important finding was that access to more information was what was needed to reduce transit-related difficulties and increase transit use. The subjects also reported a need for more information about schedules, bus numbers, routes, and locations of bus stops and terminal amenities. They thought that auditory messages would help them cross streets in order to make transfers and would also help if installed on buses and in terminals. There were many elderly people in the survey who did not make many trips, and there were also 10 subjects who had access to a household car. People with access to a household car had a much harsher view of transit use. Their estimates on how long they wait for transit were much higher than those of subjects who had no car to rely on and who used transit more often. Those who had no household car reported longer wait times for a ride (from friends or others) than in waiting for transit. These findings led us to investigate the use of auditory signage (Talking Signs® ) to determine if it would provide sufficient information needed to increase path following accuracy, decrease walking and search times, and make finding a bus easier in actual field test conditions.

To highlight what led to the desire to conduct an even larger experiment,

using more modes of transit in a larger, more urban environment, four sections

of the Santa Barbara MTD experiment are summarized.

Table 2. 3 Bus Stop, User Response Categories

“What is different from your regular method when using Talking Signs® at a bus stop?”

|

Category |

26 subjects |

|

Gives direction |

15 |

|

Gives positive identification |

15 |

|

Confidence, assurance |

14 |

|

More efficient, easier travel |

13 |

|

Don’t have to ask |

5 |

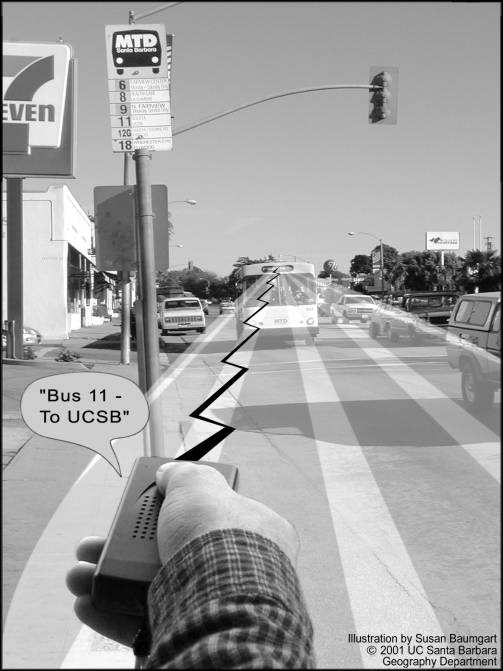

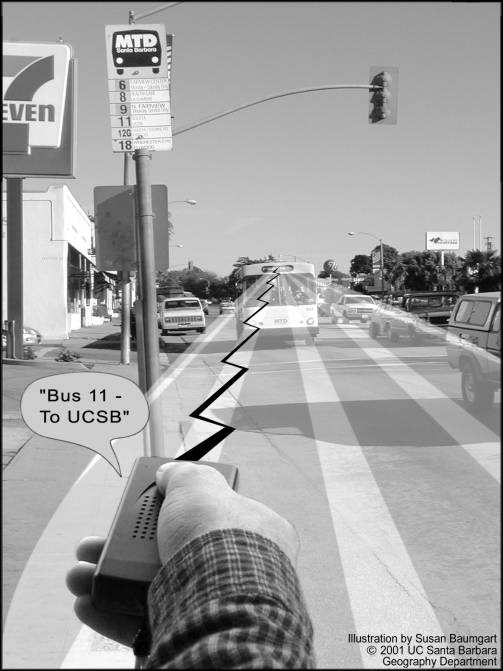

A RIAS transmitter mounted on a bus sends out a signal that can reach over 100 feet. This signal can contain the bus name, number, direction or other route information so that users know in advance which bus is coming and allows time to reach the boarding area and flag the proper bus, with complete and positive knowledge about which bus is approaching, where it goes, and the location of the entry door. Figure 2.7 shows a bus equipped with the RIAS transmitter mounted on the front.

Figure 2. 7 Using RIAS to Identify an Approaching Bus

Source: R, G. Golledge (2001) Reproduced with permission of the author.

Subjects were asked to explain the difference between RIAS and their regular methods of navigation when finding and boarding the proper bus. APPENDIX 3 lists all subjects’ comments, a few are listed here as examples.Table 2. 4 Finding and Boarding Proper Bus, User Response Categories

“What is different when using Talking Signs® to find the proper bus?”

|

Category |

26 subjects |

|

Don’t have to ask |

23 |

|

Easier, quicker |

18 |

|

Positive identification of bus |

14 |

|

Boarding location (door) information |

10 |

|

Independent |

8 |

|

Safe and secure |

3 |

|

Less stress |

3 |

At the end of the MTD terminal experiment, subjects were asked to rate their approval of various installation locations for the system. They were also asked how the system would affect their travel if it was installed on transit and at various locations. These tables are sorted with the highest ratings first. “Strongly agree” = 1, “Agree”= 2, through “strongly disagree” = 5. All responses were quite positive.

Table 2. 5 User Opinion of RIAS : Specific Locations and Travel Behavior

|

User Opinion about Talking Signs® Installations |

Ratings |

|

I would like TS installed on all buses |

1.1 |

|

I would like TS installed at bus stops |

1.1 |

|

The TS in the terminal should be made permanent |

1.1 |

|

TS on retail and other buildings would help me navigate and let me know what shopping or activities were available |

1.1 |

|

TS in the MTD terminal are very helpful |

1.2 |

|

I would like TS installed at street crossings that tell what street I am at and which direction I am facing. |

1.2 |

|

I would like TS installed at crosswalk to keep me in the walkway and tell me the WALK/DON’T WALK signal. |

1.3 |

|

User Opinion about Talking Signs® and Travel Behavior |

Ratings |

|

I would be more independent using TS |

1.2 |

|

I would feel safer when I traveled |

1.2 |

|

I could be more spontaneous when planning trips |

1.2 |

|

I would take more trips |

1.3 |

These very positive responses to the value of RIAS at bus stops and identifying

the proper bus demanded more investigation into how this system would help in

other transit environments. The equally strong ratings about the efficacy

of RIAS at various locations led to the examination of other specific types

of locations beyond that of a bus terminal and in a more varied environment.

The strong opinions that RIAS would positively affect travel behavior

led to a desire to test these sentiments in more empirical and robust experiments.

More information was needed to determine what people thought about their

current trip-making behavior and what could be done to make it more equal to

the general public.

A pre and post-test question was asked that attempted to reveal the feelings

of these vision-impaired subjects on their overall attitude toward equal access,

as it is now and how it would be if RIAS was installed throughout the environment.

The results were so strong that they also demanded more research investigating

why access was so limited and also to find what specific locations caused these

problems and what mitigating effects the addition of environmental cues, such

as location identity and direction, had on increasing access to urban opportunities.

The following two questions were asked with a five-point scale, ranging

from 1= “strongly agree” to 5 = “strongly disagree.”

Table 2. 6 ADA Compliance Measures, Pre and Post Talking Signs®

|

Rating |

|

|

Pre-test: I feel that I can get information and then find, access and use public buildings and transportation and that I enjoy the same access to buildings and transit given to the general public. |

4.5 |

|

Post-Test: If TS were installed on public buildings and transportation, I would have the same access given to the general public. |

1.3 |

These two questions revealed that people with vision impairment do not think

that they are getting the equal access that was mandated for them in 1990, and

that they feel like a system that gives environmental cues would greatly help

them to achieve this elusive goal of social equity and access. Furthermore,

in the survey, they also voiced a strong support for citywide RIAS installations

and legislation to make installation mandatory.

To better understand the problems of blind navigation, and building on past

work, there appeared to be a need to collect more data on making transfers,

about which locations were the most difficult, and where the use of RIAS could

have the most benefit. Subjects had mentioned many times how difficult

using transit was, and this inspired a decision to ask further specific questions

to determine how vision loss restricts independent travel and if RIAS could

provide more access to urban opportunities and increase access to jobs, other

activities, and travel. There appeared to be a need to collect more empirical

data about the problems of transit use and transferring between different transit

modes. More knowledge was also desired about how travel without vision

affects trip-making behavior, limitations on activity space, and participation.

Little is known about restrictions and barriers to making transfers and

how people with little or no vision perceive these barriers. There is

a need for data about how this group reacts to these barriers and if they have

a different internal resistance to distance or change. There is a need

to understand if the distance decay function is different for this group

than that exhibited by the general public. Previous research on RIAS

has either tested the efficacy of RIAS by itself or studied success when using

the system compared to users’ regular methods. There is also a

need to test the efficacy of the system using a comparison to the walking speed

of a sighted person. Clark-Carter et al. (1986) point out that,

when testing different aids for persons who are blind, in addition to measuring

errors and wrong turns, researchers must realize that the speed of the subjects

reflects their ability to use an aid to increase travel skills. By comparing

the walking and search times of blind subjects using their regular methods or

RIAS to a standard baseline derived from a sighted person, time penalties and

their mitigation with a new aid can be clearly identified. This method

also allows for a broader understanding of which locations present the biggest

problems to independent travel and which locations are more easily accessed

without sight. To be serious about understanding and then improving travel

for people who are blind, researchers must be able to identify which locations

cause the most problems for the blind and what aids or instruction can best

be used to increase travel, independence, and quality of life for this group.

Thus, the design of this research experiment evolved over many years of prior

research into the needs and travel restriction of people with limited vision.

Starting with a comprehensive interview schedule to determine attitudes and

needs, experiments progressed next to very controlled situations and then proceeded

to the first “real world” experiments. The empirical data,

plus the comments from subjects, led to the design of the present, much more

comprehensive field test.

There has been criticism in certain academic circles that disability research

is not representative of disabled people’s experiences and knowledge.

For example, Kitchin (2000) found such a lack of representation in his

research with disabled people, and he stresses that research needs to be “carefully

selected, presented in a way that is unambiguous, has a clear connection between

theory and the lives of disabled people, and needs to be acted upon” (Kitchin,

2000, p. 29) . Kitchin also states that disabled subjects are concerned

that much research is ineffectual in transferring research results to real world

improvements in their lives by helping to dismantle barriers. A main concern

was that their knowledge and experiences were “mined” by researchers,

who they never heard from again and that the research made no perceivable impact

on their lives. The subjects who participated in the previously discussed

UCSB experiments knew that their knowledge was cherished by the researchers

and was used to frame continuing research. Many of them made suggestions

after the experiment and their comments on open-ended questions led to further

research based on problems and barriers they had acknowledged. Some subjects

even refused payment for their participation, saying that the funds should go

to further research and implementation. None of the subjects quit during

any experiment, even though the tasks could become quite long, or scheduling

problems resulted in time allocation that was much longer than anticipated.

They all seemed determined to add to the body of knowledge about this

topic that directly affects their daily lives. This research was not

some strictly academic laboratory experiment that would not directly affect

them, but research into their needs to gain more information, spatial knowledge,

accessibility, freedom, independence, social equity and to improve their overall

quality of life.

| BACK TO OVERVIEW | BACK TO TABLE OF CONTENTS | NEXT SECTION |